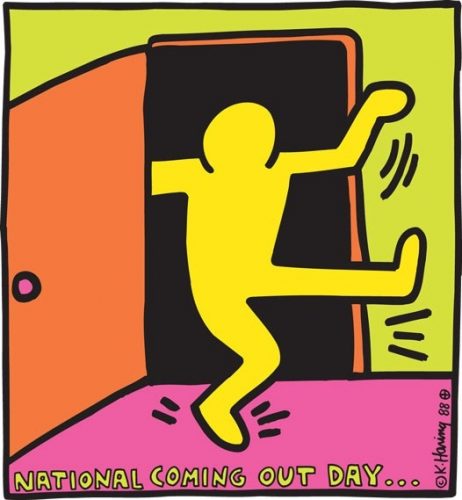

Devastated by the ruling in Bowers v. Hardwick, the LGBT rights movement asked individuals to make the fight for change a personal one. LGBT people began coming out in greater numbers than ever before—in their homes, with their friends, and in their workplaces. There was power in coming out. People who knew someone who was LGBT were more likely to support legal equality for the LGBT community.

Making the Fight Personal and Political

“. . . this [court ruling] is not the end for Gay people. The Supreme Court once said that blacks were not citizens. The black civil rights movement didn’t just end and go away. They persevered and triumphed, and so will we. . . .”

—Leonard Graff, legal director of the National Gay Rights Advocates, 1986

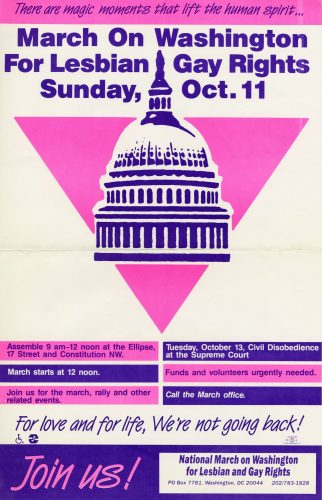

LGBT people and their allies march on Washington—some 500,000 strong—on October 11, 1987. This second march for LGBT rights (the first was in 1979) was prompted by the Bowers v. Hardwick decision, as well as the inadequate response of the federal government to the AIDS epidemic. Over 600 LGBT protestors were arrested for civil disobedience.

“Most people think they don't know anyone gay or lesbian, and in fact everybody does. It is imperative that we come out and let people know who we are and disabuse them of their fears and stereotypes.”

—Robert Eichberg, co-founder of National Coming Out Day, in 1993