Like the far-reaching effects of the Stonewall riots, the decision of the Supreme Court in the 1986 case known as Bowers v. Hardwick, has been called “the shot heard around the LGBT world.” But this one was not at all celebratory. It was, instead, a clear signal that society at large did not approve of the LGBT community.

Bowers v. Hardwick, 1986

“Condemnation of [homosexual activity] is firmly rooted in Judeo-Christian moral and ethical standards. . . . [18th-century legal scholar William] Blackstone described ‘the infamous crime against nature’ as . . . ‘a crime not fit to be named.’”

—Justice Warren Burger in Bowers v. Hardwick, 1986

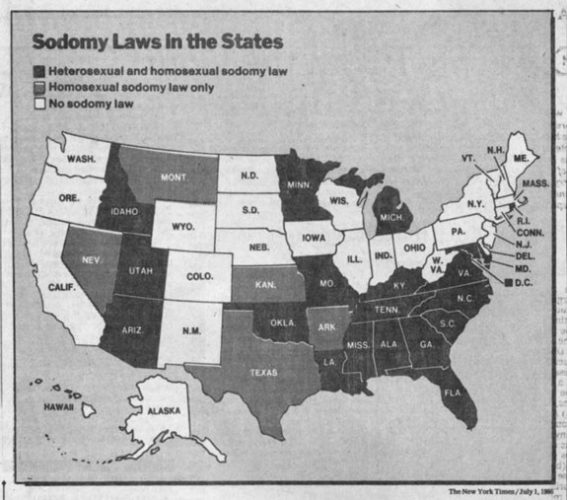

Map showing the existence of sodomy laws in the United States at the time of Bowers v. Hardwick. New York Times, July 1, 1986.

In 1982, 29-year-old Michael Hardwick is tending bar at a gay pub in Georgia. When he tosses a beer bottle into an outdoor trash bin, a policeman issues him a summons. Due to a clerical error, Hardwick misses his court date and is issued an arrest warrant. The police go to Hardwick’s apartment to serve the warrant. Allowed into Hardwick’s home by a guest, the police enter Hardwick’s bedroom and see him having intimate relations with another man. He is charged with violation of a Georgia law that says it is a crime for two men or two women to have intimate contact.

Michael Hardwick agrees to work with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which had been looking for a test case to challenge the constitutionality of laws against same-sex intimacy. Hardwick sues Michael Bowers, Georgia’s attorney general. Hardwick argues that the Supreme Court’s recognition of a right to privacy should also protect his intimate associations. The Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit holds that the Georgia statute “infringes upon the fundamental constitutional rights of Michael Hardwick.” Georgia appeals to the Supreme Court, which in November 1985 agrees to review the case. The case is commonly known as Bowers v. Hardwick.

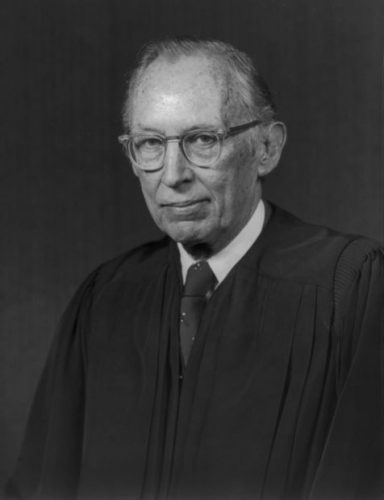

Official portraits of the 1976 U.S. Supreme Court: Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

On March 31, 1986, the case is argued in the U.S. Supreme Court, Washington, DC. On June 30, 1986, the court upholds the constitutionality of the Georgia statute by a 5-4 vote, reinstating the Georgia law that the Court of Appeals had struck down. It says that Georgia has the right to criminalize certain kinds of intimate contact. In 1990, Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., who had been considered the deciding vote in the Bowers v. Hardwick decision, tells a group of law students that he regretted voting with the majority. According to a National Law Journal account of the session, Powell said—after rereading the decision a few months after it was issued—“I thought the dissent had the better of the arguments.” The ruling would stand until struck down by the Supreme Court in Lawrence v. Texas (2003).

“HIGH COURT, 5-4, SAYS STATES HAVE THE RIGHT TO OUTLAW PRIVATE HOMOSEXUAL ACTS”

—front-page headline, The New York Times, July 1, 1986