Included here are three landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases—and just a few of the many other cases that came before the lower courts, from the 1990s to today.

In the Courts, the Debate Over Gay Rights Intensifies

“No state shall . . . deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

—from the 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution

At a 1993 demonstration in New York, gay rights activists protest against the "Don't Ask, Don't Tell" policy. Photograph by Porter Gifford.

1992: “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell"

In 1950, the Uniform Code of Military Justice sets up procedures to screen and discharge homosexuals from the armed forces, a practice which had been occurring inconsistently since the 1920s. In 1992, President Bill Clinton signs into law a compromise that became known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.” Military recruiters and supervisors can no longer ask about a person’s sexual orientation. But if it becomes known, the service member can be discharged. As a result, more than 13,000 people are dishonorably discharged from military.

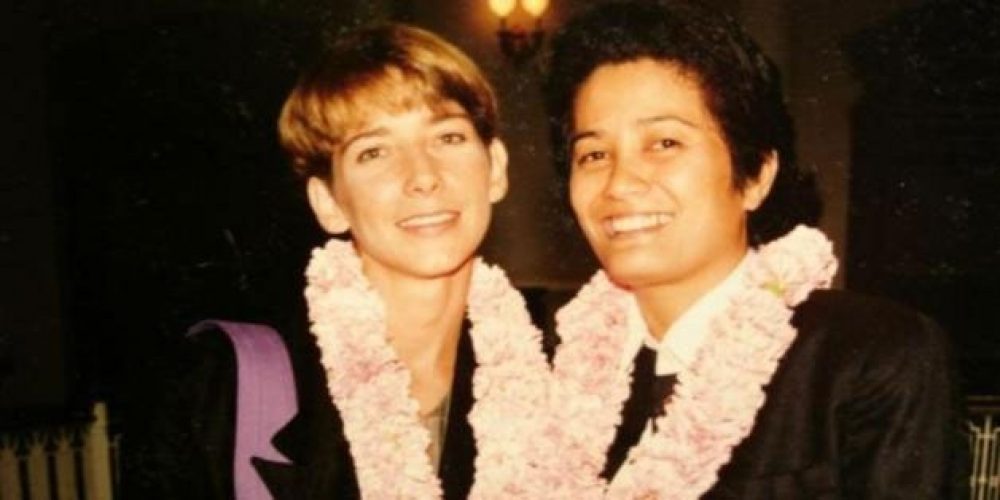

1993: Baehr v. Lewin, Hawai’i

Starting in the 1970s, lesbians and gay men take cases to the courts in pursuit of marriage equality. They cannot find a court willing to recognize their relationships. In 1993, the Supreme Court of Hawai’i changes the debate when it rules—in a first for a state Supreme Court—that same-sex couples have the right to marry under the Hawai’i constitution. In response, a movement mounts to amend the state constitution to forbid marriage by same-sex couples. That amendment passes in 1998.

Activists in Chicago, IL, protest the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), January 10, 2009. Photograph by Kevin Zolkiewicz.

1996: Federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA)

The Hawai’i decision galvanizes proponents of “traditional marriage,” who move quickly to ensure that no state would have to accept marriages of same-sex couples from other states. The traditional marriage movement produces the federal “Defense of Marriage Act” (DOMA) in 1996. It says that states are not required to recognize same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions—and that the federal government will not recognize those marriages. Dozens of states pass their own DOMAs.

1996: Romer v. Evans: Colorado’s Amend. 2

After some cities in Colorado passed laws to make it illegal to discriminate against a person because of their sexual orientation, a state referendum was passed to repeal those local laws and to change the state constitution to prohibit government agencies from adopting additional policies to protect gay men and lesbians from discrimination. The referendum, known as Amendment 2, was struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court in Romer v. Evans. The majority held that gay men and lesbians had the same right to try to pass local laws in their favor as anyone else. A statewide ban on local anti-discrimination laws, the court concluded, lacked a rational relationship to any state interest.

“Central…to our constitution’s guarantee of equal protection is the principle that government…remain open on impartial terms to all who seek its assistance.”

—Justice Anthony Kennedy in Romer v. Evans (1996)

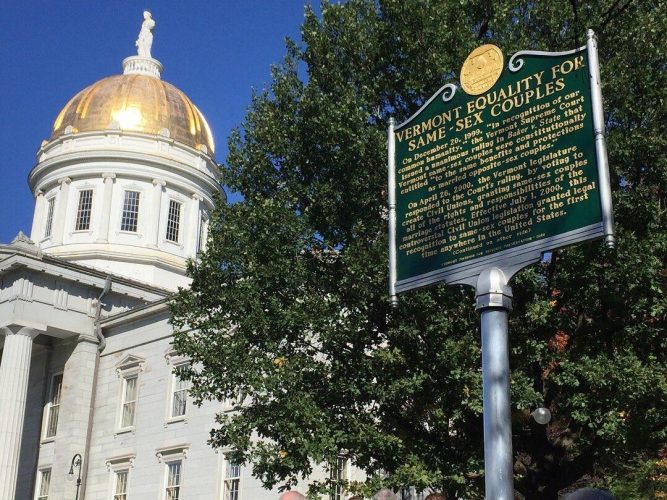

The Vermont Equality for Same-Sex Couples historic site marker at the State House in Montpelier, Vermont. Photograph by Vermont Tourism.

2000: Civil Unions: Baker v. Vermont

In 1999, the Vermont Supreme Court rules that the state’s constitution forbids the exclusion of same-sex couples from the legal protections of marriage. It orders the Vermont legislature to change the law to protect those couples. In 2000, that legislature creates “civil unions,” which are intended to be the legal equivalent of marriage.

2003: Lawrence v. Texas

In 1998, John Lawrence was arrested and charged under a Texas law that, like the Georgia law upheld in Bowers v. Hardwick (1986), made it illegal for two men or two women to have sexual relations. This time, the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the law. Five members of the Court held that Bowers v. Hardwick was wrong from the start. Lawrence v. Texas was a major milestone for advocates for LGBT equality. The case did not end discrimination, but it was a strong statement about the fundamental right of all people to live and love in a way that is true to themselves. It fueled the growing movement for equality.

“. . . adults may choose to enter upon this relationship in the confines of their homes and their own private lives and still retain their dignity as free persons.”

—Justice Anthony M. Kennedy in Lawrence v. Texas, 2003

Julie and Hillary Goodridge, the plaintiffs in the case that brought same-sex marriage to the first state in the country.

2004: Goodridge v. Department of Public Health

Massachusetts becomes the first state to allow same-sex couples to marry (after its Supreme Court ruled in 1993 that the state constitution required equality for same-sex couples). Before Goodridge, only four states had, like Hawai’i, amended their constitutions to prevent court decisions in favor of same-sex marriage. After the Massachusetts decision, 14 states more states (in 2004 alone) quickly follow suit. That same year, an effort to pass a federal constitutional amendment to ban such marriages fails in Congress.

2006: The Impact of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”

A unanimous U.S. Supreme Court ruling says that universities who do not agree with “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell”—the policy banning military service by openly gay men and lesbians—cannot keep military recruiters off their campuses in protest. If they do, they can risk losing some federal grants.

2008: California’s Supreme Court Weighs in on Marriage Equality

On May 15, the Supreme Court of California legalizes marriage for same-sex couples in the state. To overturn the decision, opponents place a state constitutional amendment on the November ballot. Known as “Proposition 8,” it passes. As a result, marriage of same-sex couples starts and stops in California in 2008. Proposition 8 is later struck down.

2010: “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” ends

After the election of Barack Obama as President, the debate over “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” comes to a head. In the face of increased pressure from the courts and the pressing military needs of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, in December 2010 Congress repeals all restrictions on military service based on sexual orientation.

2012: Transgender Equality

In a 2012 decision, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) finds that “discrimination against a transgender individual because that person is transgender is . . . discrimination ‘based on . . . sex,’ and . . . violates Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act of 1964].”

2013: United States v. Windsor

Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer met in New York City in 1963, and were together until Thea’s death in 2009. While the couple had married in Canada in 2007, after Thea died the IRS refused to recognize Edie as Thea’s wife, and said she owed thousands of dollars in taxes for the property she inherited from Thea. In U.S. v. Windsor, the Supreme Court decided that the IRS had to recognize the marriage between Edie and Thea, even though they were both women. This decision struck down the federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which said that federal agencies would not recognize marriages between same-sex couples. The decision also required the federal government to recognize couples like Edie and Thea, who had been married in a place that recognized same-sex marriages.

“[The U.S. government’s failure to recognize marriage of same-sex couples] is unconstitutional as a deprivation of the liberty of the person protected by the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution.”

—Justice Anthony M. Kennedy in U.S. v. Windsor, 2013